Video, 2015

Video, 2015

乡野调查在我的家乡常德市。

我的家乡常德市位于地球的北纬 29° 01’ 53” ,东经111° 41’ 56” ,人口截至2015年大致150万人左右。

在很小的时候去人家家里做客我印象中他们客厅都有着一幅装饰画- 一张半身的毛主席肖像,我的爷爷家也有这么一幅。这对于小时候的我毫无特别之处也没有任何一点吸引力可言。

2015年的时候,我已经在德国呆了快5年,一次回老家,从市中心的文化宫路过,在广场上,我看到了一个纪念碑,是一个国民党时期所留下的常德会战纪念碑。不知道是我历史学得不好还是遗忘得缘故,这段历史对我来说竟是空白,即使这发生的事是在我儿时生活了很久的家乡。

又过了几日我与从小一起长大的朋友聊起这件事,他带我去了一个咖啡厅,告诉我这里也许有我感兴趣的故事,老板是一位日本人。

到了店里,我们和店里的一个服务员女孩聊天,她告诉我,她会说日语,这的老板松田先生就是她的教授,并乐意帮我翻译。等过了一会儿松田先生带着一副眼镜来给我们点单,并用中文夹杂着日语和我们交流着。

他告诉了我他为什么要留在常德。

曾经在第二次世界大战的时候,常德被日军空投下夹杂着鼠疫病毒的稻艮、棉絮、布条等不明物体,鼠疫病毒既俗称黑死病。过后几天,黑死病从常德的鸡鹅巷开始蔓延至爆发。

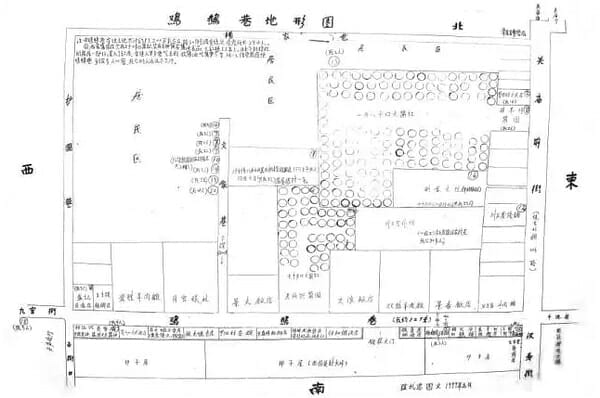

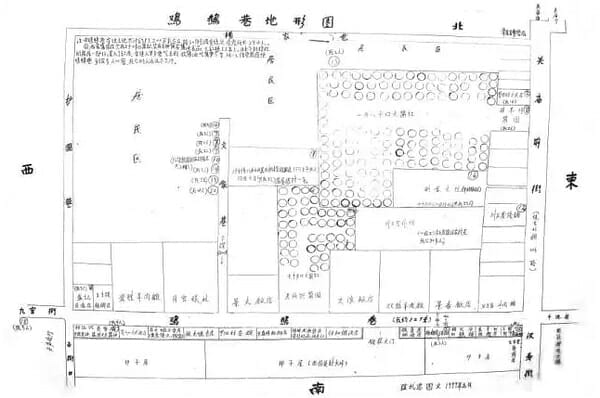

亲历者张礼忠老人手绘的鸡鹅巷地图

松田先生告诉我,2001年,他的一位朋友做为为常德细菌战受害者的辩护律师来到常德,为受害者收集证据和资料。他受他律师朋友的邀请来到常德做为摄影师专门拍摄照片。可谁能想到,这样的辩护一下就是15年。他为了能随时准备资料和联络,并能更好的帮助这些受害者便决定在这留下生活,这场历史的困局让时间和记忆都停滞了。

1942年法国作家阿尔贝·加缪贺因病退居法国南部山区帕纳里-被战争围困的孤岛。 在这里加缪开始了他的长篇小说《鼠疫》的创作。他需要找到了一个寓言体来言说法西斯这个人类自身的痼疾和人类面临的困境:

到处漫延的鼠疫病毒。

被鼠疫围困的城市。

在绝望中挣扎的人类。

我的家乡,曾经是这样的被鼠疫围困的城市,但这伤痕似乎也随着受害者的过世而被遗忘,而疫病所留下的痕迹也很难再找到了。或许网络上或日常中人们愤怒并激昂的讨论到邻国就会带有仇恨与敌对情绪,但真实发生的历史又留下了多少,与之有关的痕迹人们又愿意去了解多少。

我们并不希望遗忘,也不希望因历史的原因而造成永久的文化隔阂。或许,这些蔓延着的各类情绪的困局,将会自我保留在那一份档案, 一份文本,一个照片,一个视频中。

2015年 冬

My hometown, Changde, is located at 29° 01’ 53” north latitude and 111° 41’ 56” east longitude of the earth. As of 2015, the permanent population is roughly 1.5 million.

In my memory, when I was a child often followed my elders to visit other people’s houses, I remembered that there was a decorative painting in their living room — a portrait of Mao and at my grandfather’s house also had such a portrait. This was nothing special or attractive to me when I was a kid.

In 2015, I had been in Germany for almost 5 years. Once I went home to Changde, I passed by the Cultural Palace in the city center. On the square here, I saw a monument, a monument to the Battle of Changde from the Kuomintang period. . I don’t know if it’s because I didn’t learn history well or because I forgot it. This history is blank for me, even if it happened in my hometown where I lived a long time.

A few days later, I talked about this with a friend who grew up with me. He took me to a coffee shop and told me there might be stories I am interested in. The owner of the coffee shop is a Japanese.

When we arrived in the coffee shop, we chatted with a waiter girl. She told me that she was learning Japanese and the coffee shop owner was her professor, Mr. Matsuda and she would like to translate for me. After waiting for a while, Mr. Matsuda wore a pair of glasses to give us an order, and communicated with us in Chinese mixed with Japanese.

He told me why he wanted to stay in Changde.

During the World War II, Changde was airdropped by the Japanese army to drop unidentified objects such as rice burgundy, cotton wool, cloth strips mixed with the plague virus. The plague virus is commonly known as the Black Death. A few days later, The Black Death spread from Ji’e Alley and broke out in Changde.

Hand-painted map of Ji’e Alley by 83-year-old Zhang Lizhong, a germ war investigator

Mr. Matsuda told me that in 2001, a friend of his came to Changde as a defense lawyer for the victims of the germ warfare in Changde, to collect evidence and information for the victims. He was invited by his lawyer friend to come to Changde to take photos as a photographer. But who would have thought that such a defense would be 15 years. In order to be able to get information and contact at any time and help these victims, he decided to stay here. This historical predicament has stagnated time and memory.

In 1942, French writer Albert Camugue retired to Panari, an isolated island besieged by war, in the mountains of southern France due to illness. Here Camus started his novel “La Peste”. He needed to find an allegorical body to describe the Sith, the human disease and the predicament facing humanity:

The plague virus spread everywhere.

A city besieged by the plague.

Humans struggling in despair.

My hometown was once such a city besieged by the plague, but the scars seem to have been forgotten with the death of the victim and the traces left by the plague are hard to find as well. Perhaps people on the Internet or in daily angry and passionate discussions will bring hatred and hostility to neighboring countries, but how many traces of it are left in the real history and how much people willing to know.

We don’t want to forget, nor do we want to create a permanent cultural segregation due to historical reasons. Perhaps, the predicament of these spreading emotions will be kept in an archive, a text, a photo or a video by itself.

Winter. 2015